Ballot Access

How Does Group Identity Shape Access?

Read a PDF version of the paper here.

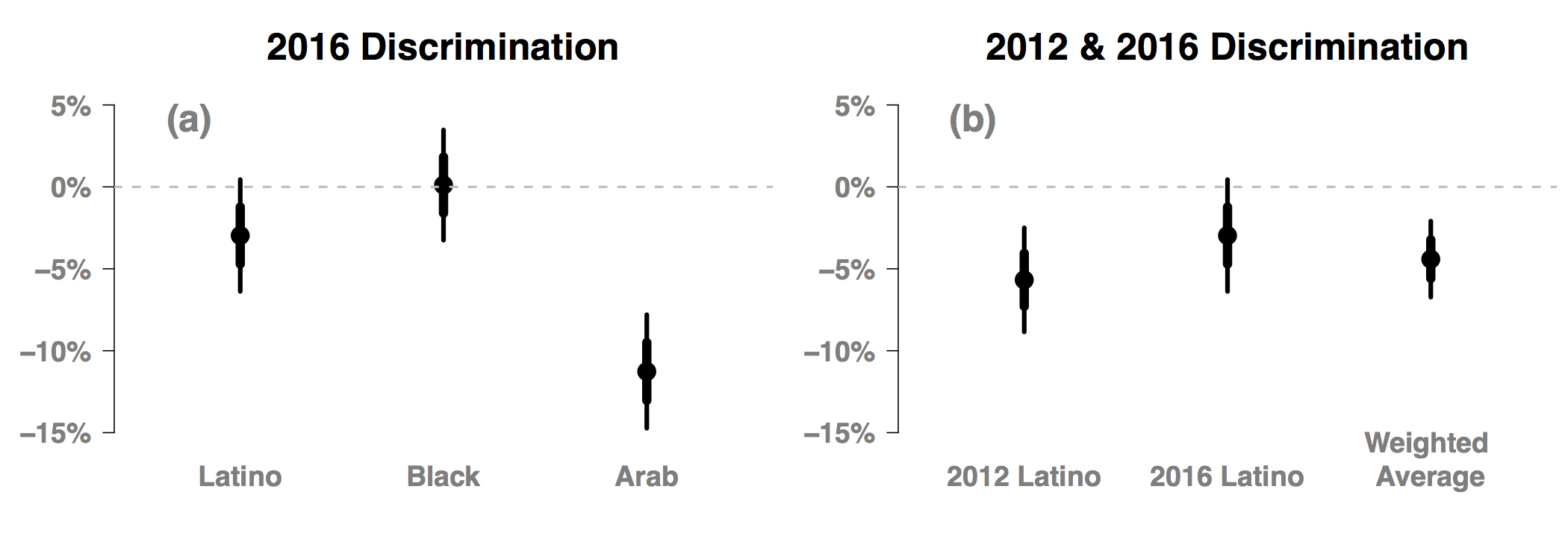

Results of an audit study conducted during the 2016 election cycle demonstrate that the bias toward Latinos observed during the 2012 election has persisted. In addition to replicating previous results, we show that Arabs face an even greater barrier to communicating with local election officials. Our study did not produce evidence of discrimination against blacks, a finding that echoes the results of other recent studies. We examine one explanation for the high level of discrimination against Arabs, that bureaucrats are politically responsive. Our findings support this explanation. In geographies that cast more votes for the Republican candidate, discrimination against Arab names was stronger.

Discrimination Against Latino Voters

Experimental evidence gathered in the 2012 General Election found that when a Latino asked a question of his Local Election Official he was less likely to receive a response than if a white man asked the exact same question. We examine whether this pattern of discriminatory behavior was limited to the 2012 election.

We find clear evidence that Latinos continue to pay a penalty. Name alone is adequate to reduce the chances of receiving information about how to vote by more than 3 percentage points.

Discrimination Against Arab Voters

Not only do Latino voters receive answers to their queries at lower rates: so too do voters who have Arab names. Indeed, an Arab name alone is sufficient to decrease the probability of having an election related question answered by more than 11 percentage points.

The magnitude of this result is arresting. Stated another way, if simply because this question was asked by an Arab rather than a White man, the request will be responded to only 3/4 as frequently.

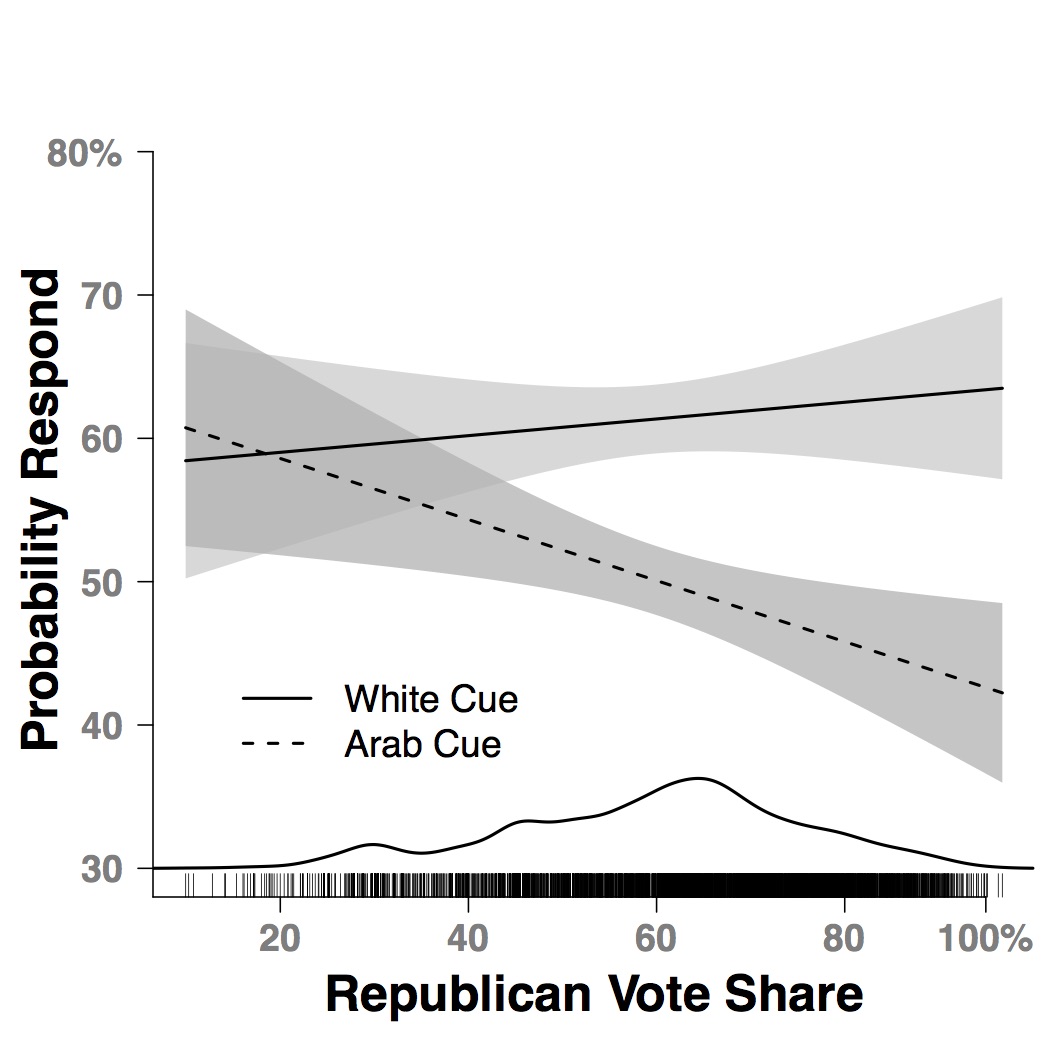

Political Pattern of Discrimination

The surprising size of the discrimination against Arab names led us to investigate what mechanisms might be leading to such a large discrepancy in treatment. As we show below, we found that discrimination was considerably stronger in discrits that voted for the Republican candidate. This suggests supports the theory that street-level bureaucrats have considerable discretion in how they execute the laws on the books.